Category : 8th Class

Rural Life Under the British Rule

After the Battle of Plassey, the British were firmly established in India both politically and economically. From traders they had become political masters. Their main interest lay in the maximisation of their profits. They reaped huge profits as traders, and now the whole country was their domain and they exploited it to the maximum.

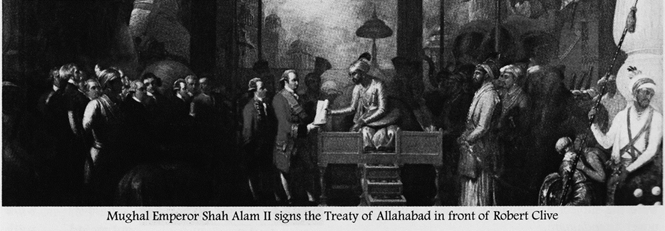

The Battle of Plassey (1757) made the British East India Company the political master of Bengal. After the Battle of Buxar (1764), the East India Company got the diwani rights for Bengal, Bihar and Orissa from the Mughal Emperor Shah Alam II in 1765. This was a great achievement on part of the Company. The Company now had the responsibility of financial administration of these territories. It had to organise the administration and increase the revenue collection.

WHY DID THE EAST INDIA COMPANY NEED FUNDS?

The primary function of the East India Company was to buy spices, cotton, indigo and other raw materials and sell them at huge profits in the European markets. The Company needed money to invest in buying these commodities.

Initially they brought gold and silver from England but later on, they thought of financing its trade from India itself. It required money to maintain huge army to fight wars against other European powers and Indian rulers. Also, it had to send money to England in order to pay dividends to the shareholders of the Company. Another major expense of the Company was paying the officers of the administrative set up in India.

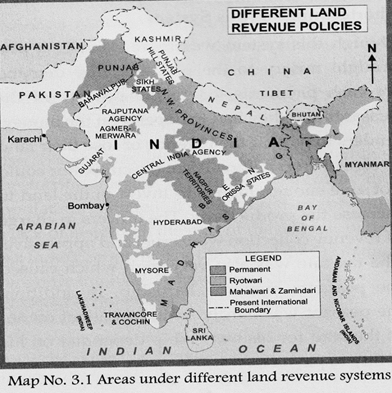

Thus, to fulfil its requirements for money, the East India Company turned its attention towards agriculture which was the chief source of income. The Company introduced new revenue policies (settlements) in agriculture. All the policies were intended to increase their profits, even if those policies harmed the peasants.

Q. why did the East India Company need increasing amounts of funds?

THE PROBLEM WITH REVENUE COLLECTION

The East India Company was a trading concern but it had acquired the right to collect revenue. The Company did not want to set up a system of revenue collection. Its main objection was to maximise revenue collection. However, the economy of Bengal was facing a decline. Farmers were unable to pay their dues. Artisans could not earn their livelihood because they had to sell their goods at lower prices to the Company. Agricultural production was also declining.

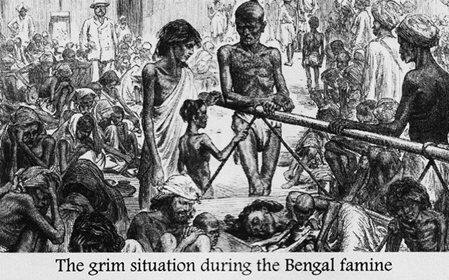

Also, Bengal was hit by a devastating famine. The terrible famine in which one-third of the population perished. It was caused mainly due to lack of insight on the part of the officials of the East India Company. The officials of the Company were only interested in revenue collection.

History Reveals

The Bengal famine and the devastation caused by it were the subject of Bankim Chandra Chatterjee's novel Anandamath.

THE NEED TO IMPROVE AGRICULTURE

Revenue collection was the main intention of the rural administration. Since this was directly related to the agricultural production, it was imperative that steps needed to be taken to increase agricultural production. Investment in land had to be encouraged. With this in mind, the Permanent Settlement Act was introduced.

Permanent Settlement Act

Lord Cornwallis introduced the Permanent settlement in 1793 in Bengal, Bihar and Orissa. The British hoped to achieve a number of objectives by this settlement. They wanted to have certainty in revenue collection and also wanted to ensure a minimum amount of revenue. Also, they wanted a system which required less supervision by the company officials. In addition, they wanted to have an alliance with the zamindars. So, it was also called the zamindari System.

Under this system the landholders and zamindars were absolute owners of the land. The farmers were reduced to the status of tenant on their land. The zamindars were entrusted with revenue collection and they had to pay a fixed amount to the British. The revenue was fixed and the British government could not increase it. However, the revenue, regardless of the harvest, had to be paid within the stipulated time. In fact, according to the Sunset Law, if payment did not come in by sunset of the specified date, the zamindari was to be auctioned.

The British benefited from the Permanent Settlement. The earning of the Company was thus assured, as there was no shortage in the revenues. The zamindars also benefited because their ownership of the land was assured. This created a class of people who would be loyal to the British.

Shortcomings of this System

This system turned out to be very harmful for the peasants and even to some zamindars. It encouraged the exploitation of the peasants by the zamindars, as they tried to increase their profits. The peasants depended on moneylenders for loans to pay the rent to the zamindars. If they failed to pay the rent, they were evicted from their ancestral lands. The zamindars also became more powerful. There were no incentives for them to improve the land or to use better raltivation techniques. They had no interest in vesting in the land.

Company followed a very rigid policy in acquiring land revenues. Also the tax collectors of Company refused any concession during the time of famines, drought or any other natural calamity. Many of the zamindars were unable to pay the revenue demanded by the British on time and as a result lost their land' since the initial revenue demand by the British was very high. These lands were then auctioned off.

Also, later at the beginning of the 19th century, the situation changed. Agriculture improved and the incomes of the zamindars increased but the company did not benefit as the revenue was permanently fixed.

Ryotwari System

This was introduced by Sir Thomas Mmiroe in 1820 in the Madras Presidency. Later, it was introduced in the Bombay Presidency too. In this system, there was a direct relationship between the government and the ryot or peasant. Every landholder was recognised as its owner and he could sell or transfer his land. He was assured of ownership of the land as long as he paid the land revenue. The revenue was fixed after the assessment of the land. In unfavourable conditions, the revenue was discounted. If the revenue was not paid, the holder was evicted. The revenue was affixed in terms of money. This system covered nearly all southern states and many western states.

Shortcomings of this System

Though this system was more flexible, it also brought misery to the peasants. The demand for cash payments led to the poverty of the peasants and they had to depend on the money-lenders to pay off the revenue or lose their land in case of crop failure. Also, the cultivator could not save enough money to invest in the land to increase the productivity. The officers in charge of revenue collection were cruel and oppressive. The tax rate was also very high which caused the peasants immense hardship. In addition, the peasant was hardly an independent owner of the land for his ownership depended on his ability to pay tax.

Mahalwari System

This system was introduced in northern India by Holt Mackenzie in 1833. It covered the states of Punjab, Awadh, Agra, parts of Orissa and Madhya Pradesh.

Under this system the tax collectors first estimated the revenue after inspecting the fields. The revenue was then calculated for the entire village called 'mahal'. The village lands were jointly held by the village community. All the members were jointly responsible for the payment of revenue. The village headman collected and paid the revenue. He got a 5 per cent commission. The peasants paid the revenue share of the whole village in proportion to their individual holdings.

This system broke down because of the very high demand for revenue. Another reason was the rigidity in revenue collection.

Q. What were the three systems of revenue collection introduced by the British in India?

EFFECTS OF THE LAND REVENUE POLICIES

The revenue policies of the British turned the rural economy upside down. The condition of the peasants became miserable and there were no welfare measures to give them relief. An important development was the emergence of the moneylender as a powerful class in rural society and economy. The peasants who were unable to pay the revenue took money on interest from the moneylender. They had to mortgage their land and pay very high rates of interest.

Ultimately, they were unable to pay back the moneylender who was no less oppressive than the British. The peasants mostly lost their land and worked as bonded labourers on the farms.

Q. what might have been the reason for sending Indians as bonded labourers to Fiji, Trinidad and Surinam and some other countries during the British rule?

COMMERCIALISATION OF AGRICULTURE

This was yet another result of the British economic policies in India towards the end of the 18th century. The commercialisation of agriculture means that the agricultural crops and goods are produced by the peasants for sale in the market and not for their own consumption. Commercialisation of agriculture in India began during the British rule.

The peasants had to pay revenue in cash. Thus, they had to sell off their harvested crops. The peasant did not get a proper price for his produce. He had to sell at a low price to get cash. This led the farmers to grow cash crops which got him more money. Cash crops like-tobacco, cotton, sugar cane, tea, coffee, jute, oilseeds, pepper, cinnamon and indigo were sold in the market for ready cash. The peasants resorted to growing these instead of food crops, to fulfil the demand for cash revenue. There was a change from cultivation for self consumption to cultivation for the market, from grains to cash crops.

The East India Company was a trading concern. They encouraged commercial agriculture by forcing the farmers to grow cash crops like-cotton, tea, sugar cane, indigo etc. This they bought at very low prices from the farmers and exported them to England and reaped huge profits.

INDIGO CULTIVATION

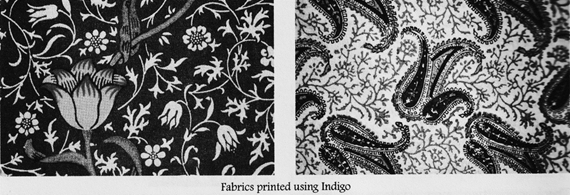

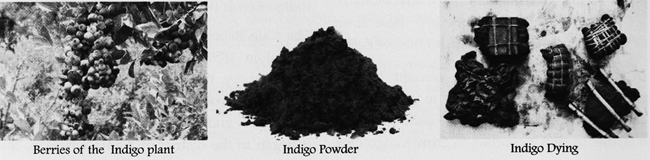

Indigo is a natural blue dye originally extracted from the indigo and woad plants. The climate of India was well suited for indigo plant cultivation. It was taken to the European markets where it was sold at high prices. Consequently, woad was used for blue dyes. However, cloth dyers preferred indigo because it gave a rich blue colour as compared to woad.

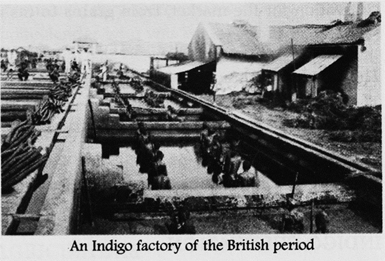

The Industrial Revolution further increased the demand for indigo, since the cloth factories in Britain spinning out bales of cloth needed indigo for dyeing. In the late 18th century, indigo supplies from the America declined. The British factories depended on the supplies from India. As India emerged as the largest exporter of indigo, the British East India Company encouraged the growth of a profitable indigo industry in Bengal and Bihar, Many Europeans sought to make their fortunes by becoming indigo planters in India. They had Indian peasant farmers grow the indigo, which was processed into dye at the planters' factories. The dye was then exported to Europe.

In India, the British forced the farmers to grow indigo. They bought it from farmers at very cheap rates, exported it to England and reaped huge profits. Earlier, the farmers grew indigo only on a small portion of their land. Later on

History Reveals

The name indigo comes from the Roman term 'indicum', which means 'a product of India'.

They were forced to cultivate indigo on their land, instead of food crops. The cultivation of indigo adversely affected the fertility of the soil. If the peasants refused to grow indigo, they were beaten ruthlessly to compel them to cultivate indigo. The fanners were unprotected and the planters were favoured by the rules of the government. The planters resorted to violent methods if the farmers refused to obey them.

There were two main systems of Indigo cultivation-nij and ryoti.

In nij cultivation, the British planter either bought land or took it on rent. Then, he hired labour to work on the land and grow indigo. So, nij cultivation was practiced only on 25 per cent of the total land under indigo cultivation.

However, this system was not without problems.

? The planters needed large, compact blocks of land. Only small plots could be acquired that were fertile.

? The planters needed plots near the indigo factories. It was difficult to evict people living near the factories and often led to conflict.

? It was difficult to secure the large amounts of labour. Mostly farmers were busy planting rice at the same time of the year.

? Large investment was required in bullocks and ploughs. For a hundred bigha farm, 200 ploughs were required. It was difficult to secure and maintain so many ploughs. Ploughs. They could not get these from farmers who required them for the rice fields.

In ryoti cultivation, Indian peasant farmers called ryots were often forced to grow indigo crop. British planters would persuade or compel a farmer to sign a contract to grow indigo on a certain portion of his land. The peasant farmers did not own their land. Instead, they rented it from the planters or from Indian landholders called zamindars. They had to grow indigo on 25 per cent of the land. They were given loans by the planter. The seed and the drill were provided by the planter while the farmer had to till the soil, sow the seeds and then look after the crop.

History Reveals

An Act was passed in 1833. According to this, the planters were free to use oppressive measures.

This system also was not without problems. The planters paid the farmers very low prices for their indigo, less than what the farmers could earn for growing rice or other crops. They could never make any profit and pay back the loans. So they fell into debt. The farmers were thus forced to enter into another contract to grow indigo, even though it was not profitable for them. Debts were never cleared and often passed from father to son.

Indigo Revolt (Blue Rebellion)

The Blue Rebellion was a peasant uprising in Bengal in 1859. The indigo cultivators were exploited by the planters, which eventually led to this revolt. The peasants rose against the oppression and they refused to grow indigo. It began in the district of Nadia where all the cultivators resorted to strike. Peasants attacked the indigo factories. The women also joined in and fought the agents of the planters. The peasants were determined not to sow indigo, pay rents or take advances to grow indigo. The strength of the farmers' resolutions was dramatically stronger than anticipated from a community victimised by brutal treatment for about half a century. The revolt spread like wildfire in Bengal. Indigo planters were executed and indigo depots were burned down. Many planters fled to avoid being caught. In many instances, the peasants were supported by the headmen of the village and the zamindars. Even the educated people supported this revolt. It was brutally suppressed. The British police massacred many peasants.

In spite of this, the revolt was fairly popular. The government immediately appointed the "Indigo Commission" for investigation. They did not want the revolt to spread further, m the commission report, E.W.L. Tower noted that "not a chest of Indigo reached England without being stained with human blood". The Commission declared that the peasants were being unfairly treated and were not being paid enough for the indigo they cultivated. It stated that peasants had to fulfil their existing contracts but could not be forced to grow indigo in the future. Now the Indigo Revolution spread to Bihar and Uttar Pradesh. The indigo peasants of Bihar revolted in Champaran in 1866. The Bengali middle class played a significant role by supporting the peasants' cause through newspapers, organizing mass meetings and supporting them in legal battles.

History Reveals

The oppression of the peasants was portrayed by Dinabandhu Mitra in his play Nil Darpsm. The play created a huge controversy. Harish Chandra Mukheriee thoroughly described the plight of the poor peasants in his newspaper The Hindu Patriot.

PROCESS OF INDIGO CULTIVATION

The indigo farms were huge and scattered near the villages. The villagers were the cultivators. A factory was situated close to the indigo plantation. It was usually near a lake or river because water was required for indigo production. Ploughing, hoeing and weeding were done till March. Sowing began in March. The sowing went on continuously because if it rained, the entire process would be spoilt. The seeds germinated in the warm climate and when the plant was a few inches high, it was safe. As it grew, its colour changed to emerald green. Caterpillars, locusts and hailstones were injurious to the plant. When the plant was about a foot high, the soil at its base was loosened to introduce air. Now the rains were welcome. By July, the stem was tall and straight. It was ready to be cut and sent to the factory.

Around the World

The Pacific Ocean was a mystery for explorers, who believed that there was a huge continent somewhere in the southern seas. Few of them wanted to venture m too far. In 1768, Captain James Cook of Britain sailed southwards and reached an unknown destination later known as New Zealand. He sailed on searching for the east coast of Australia. At last. Cook reached the coast of what he knew to be Australia.

You need to login to perform this action.

You will be redirected in

3 sec