Notes - Individual Differences and Intelligence; Thought and Language

Category : Teaching

Individual Differences and Intelligence; Thought and Language

As the term implies, individual differences are qualities that are unique; just one person has them at a time. Variation in hair color, for example, is an individual difference; even though some people have nearly the same hair color, no two people are exactly the same.

Group differences are qualities shared by members of an identifiable group or community, but not shared by everyone in society. An example is gender role: for better or for worse, one portion of society (the males) is perceived differently and expected to behave a bit differently than another portion of society (the females).

Individuals with similar, but nonetheless, unique qualities sometimes group themselves together for certain purposes, and groups unusually contain a lot of individual diversity within them. If you happen to enjoy playing soccer and have some talent for it (an individual quality), for example, you may end up as a member of a soccer team or a club (a group defined by members' common desire and ability to play soccer).But though everyone on the team fits a "soccer player's profile" at some level, individual members will probably vary in level of skill and motivation. The group, by its very nature, may obscure these signs of individuality.

Individual Styles of Learning and Thinking

All of us, including our students, have preferred ways of learning. Teachers often refer to these differences as learning styles, though this term may imply that students are more consistent across situations than is really the case. One student may like to make diagrams to help remember a reading assignment, whereas another student may prefer to write a sketchy outline instead. Yet in many cases, the students could in principle reverse the strategies and still learn the material: if coaxed (or perhaps required), the diagram-maker could take notes for a change and the note- taker could draw diagrams. Both would still learn, though neither might feel as comfortable as when using the strategies that they prefer. This reality suggests that a balanced, middle-of-the- road approach may be a teacher's best response to students' learning styles. Or put another way, it is good to support students' preferred learning strategies where possible and appropriate, but neither necessary nor desirable to do so all of the time.

Some students may prefer to hear new material rather than see it; they may prefer for you to explain something orally, for example, rather than to see it demonstrated in a video. Some prefer to be the other way round. There is evidence that individuals, including students, do differ in how they habitually think. These differences are more specific than learning styles or preferences, and psychologists sometimes call them cognitive styles, meaning typical ways of perceiving and remembering information, and typical ways of solving problems and making decisions.

Another cognitive style is impulsivity as compared to reflectivity. As the names imply, an impulsive cognitive style is one in which a person reacts quickly, but as a result makes comparatively more errors. A reflective style is the opposite: the person reacts more slowly and therefore makes fewer errors. As you might expect, the reflective style would. Better suited many academic demands of school. Research has found that this is indeed the case for academic skills that clearly benefit from reflection, such as mathematical problem solving or certain reading tasks. Some classroom or school-related skills, however, may actually develop better if a student is relatively impulsive.

Language Differences in the Classroom

Linguistic diversity is one of the elements that contribute to student diversity. Your class will have language diversity, and you will have to realize that you need to be sensitive to this linguistic diversity and adjust accordingly.

Classroom Language and Literacy Learning

Sociolinguists hold that differences in oral communication reflect social variables, such as gender, ethnicity, social class, and age. When children enter school, their mode of oral communication has been influenced by these factors; they also already work within a communication system, which consists of language structure (sound structure, inflection, syntax), content (meaning), and use (purposes of communication, appropriate forms of communication). Knowledge about meaning, language functions (pragmatics), discourse genres, and more complex syntax continue to develop during schooling and into adulthood.

Vygotsky's notion of scaffolds has played a critical role in the development of theory and research on language and literacy learning. A scaffold, of course, is an external structure that braces another structure being built. Used as a metaphor in pedagogical theory, a scaffold is an interactional mechanism for learning and development. Through dialogue and associated nonverbal interaction, teachers provide graduated assistance to novice learners as they attain ever higher levels of conceptual and communicative competence. With scaffolding, learners can experiment with new concepts and strategies in ways that would not otherwise be possible. An effective scaffold provides "support at the edge of a child's competence" defining children's zones of proximal development or their potential for new learning. "Proximal development" refers to the assumption that skills the child can display with assistance are partially developed, but cannot be employed yet without support. The wider the zone, the more capable are children to perform task; the zone is activated through dynamic connections to scaffolding...

Dialect Differences and Bilingualism

In the classroom, quite a bit happens through language. Communication is at the heart of teaching. There are two kinds of language differences- Dialect differences and bilingualism.

Dialects

A dialect is a language variation spoken by a particular ethnic, social or regional group and is an element of a group's collective identity. The rules for a language define how words should be pronounced, how meaning should be expressed, and the ways the basic parts of speech should be put together to form sentences. Dialects appear to differ in their rules in these areas, but it is important to remember that these differences are not errors. Each dialect within a language is just as logical, complex and rule-governed as the standard form of the language (often called standard speech). An example of this is the use of double negative. The double negative is required by the grammatical rules. To say" I don't want anything" in Spanish, you must literally say, "I don't want nothing".

Dialects and teaching

What does all of this mean for teachers? How can they cope with linguistic diversity in the classroom? First, they can be sensitive to their own possible negative stereotypes about children who speak a different dialect. Sometimes teachers who hold negative attitudes towards such children give lower ratings to student on different tests. This can be avoided as it affects the morale of students leading to low productivity.

Bilingualism

The majority of children around the world are bilingual, meaning that they understand and use two languages. Even in the United States, which is a relatively monolingual society, more than 47 million people speak a language other than English at home. In larger communities throughout the United States, it is therefore common for a single classroom to contain students from several language backgrounds at once. In classrooms as in other social settings, bilingualism exists in different forms and degrees. At one extreme are students who speak both English and another language fluently; at the other extreme are those who speak only limited versions of both languages. In between are students who speak their home (or heritage) language much better than English, as well as others who have partially lost their heritage language in the process of learning English. Commonly, too, a student may speak a language satisfactorily, but be challenged by reading or writing it - though even this pattern has individual exceptions. Whatever the case, each bilingual student poses unique challenges to teachers.

Primary education should be bilingual. Successive stages of bilingualism are expected to build up to an integrated multilingualism. The first task of the school is to relate the home language to the school language. Thereafter, one or more languages are to be integrated, so that one can move into other languages without losing the first one. This would result in the maintenance of all languages, each complementing the other.

Mother-tongue should be the medium of instruction all through the school, but certainly in the primary school. The Working Group on the Study of Languages constituted by NCERT in 1986 recommends in its report that 'the medium of early education' should be the mother tongue of the learners.

According to UNESCO's Educational Position Paper (2003), mother-tongue instruction is essential for initial instruction and literacy and should be extended to as late a stage in education as possible. Some studies have shown that children who study through the mother-tongue medium do not suffer any disadvantage, linguistic or scholastic, when they compete with their English- medium counterparts. The mother-tongue as a medium of instruction can eliminate the linguistic and cultural gaps caused by the difference between school language and home language, i.e. the reference point might be a minor, or minority, or major language. Researchers also point out that the reason for 26 per cent of the dropouts at the level of elementary education is the 'lack of interest in education' caused partly by the lack of cultural content in educational programs; language is not only a 'component of culture' but also a 'carrier of culture'.

Cultural Differences in Language Use: The Indian Context

In a country like India, most children arrive in schools with multilingual competence and begin to drop out of the school system because, in addition to several other reasons, the language of the school fails to relate to the languages of their homes and neighborhoods. Most children leave schools with dismal levels of language proficiency in reading comprehension and writing skills, even in their own native languages.

Some reasons that are primarily responsible for these low levels of proficiency include:

Language, Attitudes and Motivation

The attitudes and motivation of learners often play an important role in all language learning. Similarly, the attitudes of the teacher and parental encouragement may contribute to successful language learning. Researchers working in the area of second or foreign language learning have identified several social psychological variables that influence the learning of a second language.

Some of these variables are:

(a) aptitudes (b) intelligence;

(c) attitudes; (d) motivation and motivational intensity;

(5) authoritarianism; and (6) ethnocentrism

Language and Gender

The issue of gender concerns not half but the whole of humanity. Over a period of time, language has coded in its texture a large number of elements that perpetuate gender stereotypes. Several studies have addressed the issues that center round language and gender. Detailed analysis of male-female conversation has also revealed how men use a variety of conversational strategies to assert their point of view.

'

The received notions of what it means to be 'masculine' or 'feminine' are constantly reconstructed in our behavior and are, sometimes unwittingly perhaps, transmitted through our textbooks. Indeed, the damage done by the 'gender construction of knowledge' is becoming increasingly obvious. Language, including illustrations and other visual aids, plays a central role in the formation of such knowledge and we need to pay immediate attention to this aspect of language. It is extremely important that textbook writers and teachers begin to appreciate that the passive and deferential roles generally assigned to women are socio-culturally constructed and need to be destroyed as quickly as possible. The voices of women in all their glory need to find a prominent place in our textbooks and teaching strategies.

Minor, Minority and Tribal Languages

The underprivileged speakers of minor, minority, and tribal languages often suffer severe linguistic deprivation. It is important for us to realize that the major languages of this country, including English, can flourish only in the company of and not at the cost of minor languages. The ideological position that the development of one language also helps in the development of other languages leads one to expect that the development of even some of the languages could provide a marked impetus to the rest of the languages in the case of the linguistically diverse tribal areas, and spur the speech communities to consciously strive in that direction.

Needless to say, every teacher will evolve his or her own specific method depending on a variety of social, psychological, linguistic, and classroom variables. The new dispensation must empower the teacher to use his or her space in the classroom more effectively and innovatively. Some of these basic principles include:

Gender-role Identity

The word gender usually refers to traits and behaviors that a particular culture judges to be appropriate for men and for women. Gender-role identity is the image each individual has of himself or herself as masculine or feminine in characteristics-a part of self-concept. People with "feminine" identity would rate themselves high on characteristics usually associated with females, such as "sensitive" and low on characteristics traditionally associated with males, such as "forceful". Most people see themselves in gender-typed terms, as high on either masculine or feminine characteristics. Some children and adults, however, are more androgynous-they rate themselves high on both masculine and feminine traits. They can be forceful or sensitive, depending on the situation. Recently, some psychologists have suggested that measures of androgyny actually assess instrumental (goal-directed) and expressive (social-emotional) traits, not masculine and feminine traits.

Gender bias in the Curriculum

During the elementary school years, children continue to learn about what it means to be male or female. Unfortunately schools often foster these gender biases in a number of ways. Most of the textbooks produced for the early grades still portray both males and females in stereotyped roles. One study found that there were four times more stories about male characters than about females. In addition, the females tended to be shown in the home, behaving passively and expressing fear or incompetence. Though the textbooks have improved in terms of gender bias, there still are more males in the titles and the illustrations, and the characters (especially the boys) continue to behave in stereotypic ways. Boys are more aggressive and argumentative, and girls are more expressive and affectionate. Videos, computer programs, and testing materials also often feature boys more than girls.

Sex Differences in Mental Abilities

From infancy through the preschool years, most studies find few differences between boys and girls in overall mental and motor development or in specific abilities. During the school years and beyond, psychologists find no differences in general intelligence on the standard measures- these tests have been designed and standardized to minimize sex differences. However, scores on some tests of specific abilities show sex differences. For example, from elementary through high school, girls score higher than boys on tests of reading and writing and fewer girls remediation in reading.

Gender Differences in the Classroom

Although there are many exceptions, boys and girls do differ on average in ways that parallel conventional gender stereotypes and that affect how the sexes behave at school and in class. The differences have to do with physical behaviors, styles of social interaction, academic motivations, behaviors, and choices. They have a variety of sources?primarily parents, peers, and the media. Teachers are certainly not the primary cause of gender role differences, but sometimes teachers influence them by their responses to and choices made on behalf of students.

There has been quite a bit research on teacher's treatment on male and female students. Some female teachers interact more with boys than with girls. This is true from preschool to college. Teachers ask more questions of males, give males more feedback (praise, criticism, correction), and give more specific and valuable comments to boys. As girls move through grades, they have less and less to say.

The imbalances of teacher attention given to boys and girls are particularly dramatic in math and science classes. In one study, boys were questioned in science class 80% more often than girls. Teachers wait longer for boys to answer and give more detailed feedback to boys. Boys also dominate the use of equipment in science labs, often dismantling the apparatus before the girls in the class have a chance to perform the experiments.

Academic and Cognitive Differences in Gender

On average, girls are more motivated than boys to perform well in school, at least during elementary school. As youngsters move into high school, they tend to choose courses or subjects conventionally associated with their gender?math and science for boys, in particular, and literature and the arts for girls. By the end of high school, this difference in course selection makes a measurable difference in boys' and girls' academic performance in these subjects. But again, consider my caution about stereotyping: there are individuals of both sexes whose behaviors and choices run counter to the group trends. Differences within each gender group generally are far larger than any differences between the groups. A good example is the "difference" in cognitive ability of boys and girls. Many studies have found none at all. A few others have found small differences, with boys slightly better at math and girls slightly better at reading and literature. Still other studies have found the differences not only are small, but have been getting smaller in recent years compared to earlier studies.

How teachers influence gender roles? Teachers often intend to interact with both sexes equally, and frequently succeed at doing so. Research has found, though, that they do sometimes respond to boys and girls differently, perhaps without realizing it. Three kinds of differences have been noticed. The first is the overall amount of attention paid to each sex; the second is the visibility or "publicity" of conversations; and the third is the type of behavior that prompts teachers to support or criticize students.

Attention Paid

In general, teachers interact with boys more often than with girls by a margin of 10 to 30 percent, depending on the grade level of the students and the personality of the teacher. One possible reason for the difference is related to the greater assertiveness of boys that I already noted; if boys are speaking up more frequently in discussions or at other times, then a teacher may be "forced" to pay more attention to them. Another possibility is that some teachers may feel that boys are especially prone to getting into mischief, so they may interact with them more frequently to keep them focused on the task at hand. Still another possibility is that boys, compared to girls, may interact in a wider variety of styles and situations, so there may simply be richer opportunities to interact with them. This last possibility is partially supported by another gender difference in classroom interaction, the amount of public versus private talk.

Public Talk versus Private Talk

Teachers have a tendency to talk to boys from a greater physical distance than when they talk to girls. The difference may be both a cause and an effect of general gender expectations, expressive nurturing is expected more often of girls and women, and a businesslike task orientation is expected more often of boys and men, particularly in mixed-sex groups (Whatever the reason, the effect is to give interactions with boys more "publicity". When two people converse with each other from across the classroom, many others can overhear them; when they are at each other's elbows, though, few others can overhear.

Distributing praise and criticism

In spite of most teachers' desire to be fair to all students, it turns out that they sometimes distribute praise and criticism differently to boys and girls. The tendency is to praise boys more than girls for displaying knowledge correctly, but to criticize girls more than boys for displaying knowledge incorrectly. Another way of stating this difference is by what teachers tend to overlook: with boys, they tend to overlook wrong answers, but with girls, they tend to overlook right answers. The result (which is probably unintended) is a tendency to make boys' knowledge seem more important and boys themselves more competent. A second result is the other side of this coin: a tendency to make girls' knowledge less visible and girls themselves less competent.

The Indian Context- Position Paper National Focus Group

(On gender issues in Education, NCERT-2006)

Gender is the most pervasive form of inequality, as it operates across all classes, castes and communities. The dropout rates of girls, especially from the marginalized sections of society and the rural areas continues to be sad-9 out of every 10 girls ever enrolled in school do not complete schooling, and only 1 out of every 100 girls enrolled in Class 1 reaches Class XII in rural areas. Factors cited for dropout include poor teaching, non-comprehension, difficulties of coping and high costs of private tuition or education. Despite the education system's focused efforts to include girls, it continues to "push out" those who are already within. Clearly issues of curriculum and pedagogy require equal and critical attention, in addition to enrolment.

Work on gender sensitization and awareness building has acquired complacency given that it circles around issues of enrolment, the relative absence of female figures or removal of gendered stereotypes in textbooks. In order to move forward serious inquiry into curricula, content, the gendered construction of knowledge, as well as a more critical and pro-active approach to issues of gender is necessary. Gender has to be recognized as a cross-cutting issue and a critical marker of transformation; it must become an important organizing principle of the national and state curricular framework as well as every aspect of the actual curricula.

Implications for girls as students: Once girls are able to access schools, the assumption is that as girls and women have entered the public sphere, empowerment will automatically follow. Their life chances will expand and they will be in a position to take greater control of their lives. But the complexity lies in the fact that schools themselves create boundaries that curb possibilities. The content, language, images in texts, the curricula, and the perceptions of teachers and facilitators have the power to strengthen the hold of patriarchy.

Schooling has become another form of domestication. For example, school textbooks depict this gender based domestic division of labor. In the classroom too, just as dalit children are expected to perform the menial tasks, girls are often relegated the work of cleaning and sweeping, reinforcing the gendered division of labor. The aspirations of young girls are unrelated to their actual intellectual and cognitive abilities. The work of gender sensitization and awareness building has acquired complacency and is limited to the issues of enrolment of girls, and to the relative absence of female figures or proliferation of gendered stereotypes in text books. Such work is clearly inadequate and there is an urgent need now for serious inquiry into curricula, content, and the gendered construction of knowledge.

SC /ST girls' schooling, gendered labor and socialization:

Various educational incentives have undoubtedly facilitated the educational progress of scheduled castes and scheduled tribes, particularly in the last two decades. However, they continue ?to lag behind educationally and there is great unevenness between different state and regions. The of SC/ST are unable to send their children to 'free' schools because of costs other than the tuition fee and of forgone income from the children's work. However, educationally the most vulnerable are girls. Dalit girls' educational aspirations are decisively shaped by labor requirements of the domestic and public economies: In the caste/gendered segmentation of the labor market women are disproportionately found in agricultural/rural labor, traditional domestic, low skilled, low status, or caste related (sweeping - scavenging) services in rural sectors. In urban sectors, poor women are located in lowly unskilled, low status feminized service sectors in urban informal Educational careers of most dalit girls are shaped by this structure. Even those who can meet the expenditure of the education of their children, spend less on the schooling of their daughters than the sons. The expenses of dowry compound the problem, and the chances of girls being educated is reduced further.

Addressing the Talented, Creative, Specially-abled learners or Gifted Children

Children and youth with outstanding talent perform or show the potential for performing at remarkably high levels of accomplishment when compared with others of their age, experience, or environment. These children and youth exhibit high capability in intellectual, creative, and/ or artistic areas, possess an unusual leadership capacity, or excel in specific academic fields. They require services or activities not ordinarily provided by schools. Outstanding talents are present in children and youth from all cultural groups, across all economic strata, and in all areas of human endeavor.

Truly gifted children are not the students who simply learn quickly with little effort. The work of gifted students is original, extremely advanced for their age, and potentially of lasting importance. These children may read fluently with little instruction by age 3 or 4. They may play a musical instrument like a skillful adult, turn a visit to a grocery store into a mathematical puzzle, and become fascinated with algebra when their friends are having trouble carrying in addition.

A classic study of the characteristics of the academically and intellectually gifted was started decades ago by Lewis Terman and colleagues. This huge project is following the lives of 1,528 gifted males and females and continued until the year 2010. The subjects all have IQ scores in the top 1% of the population (140 or above on the Stanford-Binet individual test of intelligence. They were identified on the basis of these test scores and teacher recommendations.

Terman and colleagues found that these gifted children were larger, stronger and healthier than the norm. They often walked sooner and were more athletic. They were more emotionally stable than their peers and became better-adjusted adults than the average. They had lower rates of delinquency, emotional difficulty, divorce, drug problems and so on.

Recognizing Sifts and Talents

Teachers are successful only about 10% to 50% of the time in picking out the gifted children in their classes. These seven questions, taken from an early study of gifted students/ are still good guides today.

Group achievement and intelligent tests tend to underestimate the IQs of very bright children. Group tests may be appropriate for screening, but they are not appropriate for making placement decisions. Many psychologists recommend a case study approach to identifying gifted students. This means gathering many kinds of information, test scores, grades, examples of work, projects and portfolios, letters or ratings from teachers, self-ratings, and so on. Especially for recognizing artistic talent, experts in the field can be called in to judge the merits of a child's creations. Science projects, exhibitions, performances, auditions, and interviews are all possibilities. Students with remarkable abilities in one area may have much less impressive abilities in others.

Teaching gifted children

Some educators believe that gifted students should be accelerated- moved quickly through the grades or through particular subjects. Other educators prefer enrichment-giving the student? Additional, more sophisticated, and more thought-provoking work, but keeping them with their age-mates in school.

Many people object to acceleration, but most careful studies indicate that truly gifted student? Who begin primary, elementary, high school, college, or even graduate school early do as well as and usually better than non-gifted students who are progressing at the normal pace. Social and emotional adjustment does not appear to be impaired. Gifted students tend to prefer the company of older playmates and may be miserably bored if kept with children of their own age. Skipping grades may not be the best solution for a particular student. An alternative to skipping grades is to accelerate students in one or two particular subjects or allow concurrent enrolment in advance- placement courses, but keep them with peers for most classes.

Teaching methods for gifted students should encourage abstract thinking (formal-operation; thought), creativity, reading of high-level and original texts, and independence not just the learning of greater quantities of facts. On approach that does not seem promising with gifted student? Cooperative learning in mixed abilities groups. Gifted students tend to learn more when they work in groups with other high ability peers. In working with gifted and talented students, a teacher must be imaginative, flexible, tolerant and unthreatened by the capabilities of these students.

THE EDUCATION OF GIFTED CHILDREN

Identification

The identification of gifted children is a big problem for educators. It is inextricably tied to One?s definition of and beliefs about the nature of giftedness and also to the programs and services that are put into place for children who have been identified as gifted. For example, if you believe strongly that the aim of identification is to find children who have the potential to become creative producers in adulthood, identification procedures might include a focus on demonstration of exceptional creative work in school coupled with task persistence and motivation to produce unusual products at a high level. On the other hand, if your beliefs about giftedness are that it is exceptional intellectual ability regardless of actual achievement or performance, measures such as IQ scores could be used for identification, and you would aim to include children with high ability yet low school achievement. If you subscribe to an educational definition of giftedness and believe that gifted children are those for whom the typical school curriculum is inadequate, you would use measures of achievement to find students who are able to perform beyond their current school placement in the subjects typically taught in schools. If you subscribe to a multiple intelligences view or" ability, you would want to establish identification procedures to find children with talent in the various domains and provide programs to help them develop that talent.

INTELLIGENCE

According to Wechsler, intelligence is the aggregate or global capacity of the individual to act purposefully, to think rationally and to deal effectively with his environment. Researchers have developed various types of models of intelligence. Some of the models of intelligence are as given below:

Unitary or Monarchy Theory

This theory has been defined by Binet. According to this theory intelligence consists of only one factor namely a fund of intellectual competence which is universal for all the activities of a person. But in our practical life we see contrary to this. A genial statistics professor may be absent minded or socially ill-adjusted. A student very good at conducting Science experiments may not be equally competent in learning languages. Hence, it is suggested that the unitary approach is too simple and a complex model is needed to explain intelligence satisfactorily.

Two-factor theory of intelligence

Charles Spearman suggested that there is one mental attribute, which he called g or general intelligence that is used to perform any mental test, but that each test also requires some specific abilities in addition to g. For example, memory for a series of numbers probably involves both g and some specific ability for immediate recall of what is heard. Spearman assumed that individuals vary in both general intelligence and specific abilities, and that together these factors determine performance on mental tasks. For example, an individual's performance in English could be partly due to the general factor and partly due to some kind of specific ability in language.

Multi-factor theory of Thorndike

Thorndike did not believe in the general factor. According to the theory intelligence is said to be constituted of multitude of separate factors or elements each being a minute element or ability. In other words, intelligence is the sum total of specific capacities. There is no generality to intelligence but rather commonality in the acts that people perform. A mental act involves a number of these minute elements operating together. If any two tasks are correlated, the degree of correlation is due to the common elements involved in the two tasks.

Thorndike distinguished 4 attributes of intelligence. They are:

Level: refers to the difficulty of a task that can be solved. If all test items are arranged in an order of increasing difficulty, then the height that we can climb on the ladder of difficulty decides our level of intelligence.

Range: This refers to the number of tasks at any given degree of difficulty that we can solve. An individual possessing a given level of intelligence should be able to solve the whole range of task at that level.

Area: It refers to the total number of situations at each level to which the individual is able to respond. Area is the summation of all the ranges at each level of intelligence processed by an individual.

Speed: This is the rapidity with which an individual can respond to items.

Group-factor theory of Thurston

Thurston extended Spearman's two-factor theory into multi-factor theory. According to this theory, certain mental operations have in common a PRIMARY factor that gives them psychological and functional unity and which differentiates them from other mental operations. These mental operations then constitute a group. A second group of mental operations has its own unifying Primary factor; a third group has a third Primary factor and so on. Each of these primary factors is said to be relatively independent of others. From further analysis, Thurston and his associate? Concluded that seven Primary mental abilities emerged clearly enough for identification and used in test designing. They are:

Structure of Intellect by Guilford

Guilford and his associates proposed the theory of Structure of Intellects on their attempt of factor analysis. This theory represents cubical model. This model provides for 120 factors- intelligence.

Guilford suggests that mind is composed of 3 major dimensions namely

Operations

Contents

Products

Cognitive Theories of Intelligence

Another view that has stood the test of time is Raymond Cattell and John Horn's theory of fluid and crystallized intelligence.

Fluid intelligence

It is dependent on neurological development and is relatively free form the influences of education and culture. In other words, it is derived more from biological and genetic factors and les influenced by training and experience. This type of intelligence is put to use when facing new and strange situations requiring adaptation, comprehension, reasoning, problem-solving and identifying relationships etc. It reaches its full development by the end of an individual's adolescence.

Crystallized intelligence

On the other hand, is not functioning of one's neurological development and, is, therefore not innate like fluid intelligence. Rather, it is especially learned and is, therefore dependent on education and culture. It involves one's acquired fund of general information consisting of knowledge and skills essential for performing different tasks in one's day to day life. It can be identified through one's fund of vocabulary, general knowledge of world affairs, the knowledge of customs, traditions, and rituals, manner of behaving in society, handling of machines and tools, craftsmanship and art, computation and keeping of accounts and various other such tasks requiring knowledge, experience and practice.

Measurement of Intelligence

In 1904, Alfred Binet was confronted with the following problem by the minister of public instruction in Paris. How can students who will need special teaching and extra help be identified early in their school careers, before they fail in regular classes? Binet was also a political activist very much concerned with the rights of children. He believed that having an objective measure of learning ability could protect students from poor families who might be forced to leave school because they were the victims of discrimination and assumed to be slow learners.

Binet and his collaborator Simon wanted to measure not only school achievement, but the intellectual skill students needed to do well in school. After trying many different tests and eliminating items that did not discriminate between successful and unsuccessful students, Binet and Simon finally identified 58 tests, several for each age group from 3 to 13. The tests of Binet tests allowed the examiner to determine a mental age for a child. A child who succeeded on the items passed by most 6-year olds, for example, was considered to have a mental age of 6, whether the child was actually 4, 6, or 8 years old.

The concept of intelligence quotient, or IQ, was added after the test of Binet was brought to the US and revised at Stanford University to give us the Stanford-Binet test. An IQ score was computed by comparing the mental-age score to the person's actual chronological age. The formula was

![]()

Group versus Individual IQ Tests

The Stanford-Binet is an individual intelligence test. It has to be administered to one student at a time by a trained psychologist and takes about two hours. Most of the questions are asked orally and do not require reading or writing. A student usually pays closer attention and is more motivated to do well when working directly with n adult.

Psychologists also have developed group tests that can be given to whole classes or schools. Compared to an individual test, a group test is much less likely to yield an accurate picture of any one person's abilities. When students take tests in a group, they may do poorly because they do not understand the instructions, because they have trouble reading, because their pencils break, or they lose their place on the answer sheet, because other students distract them, or because the answer format confuses them.

There are more sophisticated versions of the IQ tests. One is the SAT. Its name originally stood for Scholastic Aptitude Test., although with the passage of time the meaning of the acronym changes- it became the scholastic assessment test. And more recently, it has been reduced to the plain old SAT-just the initials. The SAT purports to be a similar kind of measure and if you add Up a person's verbal and math score, as is often done, you can rate him or her along a single intellectual dimension.(Recently, writing and reasoning components have been added). Programs for the gifted use that kind of measure,

Along with this one-dimensional view, of how to assess people's minds, comes a corresponding view of school, which is the "uniform view". A uniform school features a core curriculum- a set of facts that everyone should know. The better students, perhaps those with higher IQs are allowed to take courses that call on critical reading, calculations and thinking skills, hi the uniform school there are regular assessments, using paper and pencil instruments, of the IQ or SAT variety. These assessments yield reliable rankings of people; the best and the brightest get into the better college' and perhaps they will also get better rankings in life.

The uniform school sounds fair-after all, everyone is treated in the same way. But this supposed rational was completely unfair. The uniform school picks out and is addressed to a certain kind of mind-we might call it provisionally the IQ or SAT mind.

MULTIPLE INTELLIGENCES

Howard Gardner's theory of multiple intelligences

Gardner proposes that there are eight different forms of intelligence, each of which functions independently of the others. Each person has a mix of all eight abilities - more of one and less of another, that helps to constitute that person's individual cognitive profile. Since most tasks, including most tasks in classrooms require several forms of intelligence and can be completed in more than one way, it is possible for people with various profiles of talents to succeed on a task equally well. In writing an essay, for example, a student with high interpersonal intelligence but rather average verbal intelligence might use his or her interpersonal strength to get a lot of help and advice from classmates and the teacher. A student with the opposite profile might work well alone, but without the benefit of help from others. Both students might end up with essays that are good, but good for different reasons.

Gardener grouped the MIs into 4 categories: those valued in the school; those valued in the arts; those connected to the personal; and those connected to the environment.

Multiple intelligences according to Howard Gardner

|

Form of intelligence |

Examples of activities using the intelligence |

|

Linguistic: verbal skill; ability to use language well |

|

|

Musical: ability to create and understand music |

|

|

Logical: Mathematical: logical skill; ability to reason, often using mathematics |

|

|

Spatial: ability to imagine and manipulate the arrangement of objects in the environment

|

|

|

Bodily: kinesthetic: sense of balance; coordination in use of one's body |

|

|

Interpersonal: ability to discern others' nonverbal feelings and thoughts |

|

|

Intrapersonal: sensitivity to one's own thoughts and feelings |

|

|

Naturalist: sensitivity to subtle differences and patterns found in the natural environment |

|

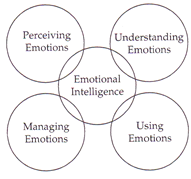

EMOTIONAL INTELLIGENCE

Emotional intelligence can be defined as the ability to perceive control and evaluate own and other people's emotions, to discriminate between different emotions and label them appropriately and to use emotional information to guide thinking and behavior. There are three main models of El:

1. Ability model

2. Mixed model (usually subsumed under trait El)

3. Trait model

In 1983, Howard Gardner introduced the idea that traditional types of intelligence, such as IQ, fail to fully explain cognitive ability. He introduced the idea of multiple intelligences which included both interpersonal intelligence (the capacity to understand the intentions, motivations and desires of other people) and intrapersonal intelligence (the capacity to understand oneself, to appreciate one's feelings, fears and motivations). The first use of the term "emotional intelligence" is usually attributed to Wayne Payne's doctoral thesis. However, the concept of emotional intelligence became widely known with the publication of Go leman?s Emotional Intelligence Why it can matter more than IQ.

Factors of Emotional Intelligence

The Four Branches of Emotional Intelligence

Salovey and Mayer proposed a model that identified four different factors of emotional intelligence: the perception of emotion, the ability reason using emotions, the ability to understand emotion and the ability to manage emotions.

1. Perceiving Emotions: The first step in understanding emotions is to perceive them accurately. In many cases, this might involve understanding nonverbal signals such as body language and facial expressions.

2. Reasoning with Emotions: The next step involves using emotions to promote thinking and cognitive activity. Emotions help prioritize what we pay attention and react to; we respond emotionally to things that gamer our attention.

3. Understanding Emotions: The emotions that we perceive can carry a wide variety of meanings. If someone is expressing angry emotions, the observer must interpret the cause of their anger and what it might mean. For example, if your boss is acting angry, it might mean that he is dissatisfied with your work; or it could be because he got a speeding ticket on his way to work that morning or that he's been fighting with his wife.

4. Managing Emotions: The ability to manage emotions effectively is a crucial part of emotional intelligence. Regulating emotions, responding appropriately and responding to the emotions of others are all important aspect of emotional management.

According to Salovey and Mayer, the four branches of their model are. "Arranged from more basic psychological processes to higher / more psychologically integrated processes. For example, the lowest level branch concerns the (relatively) simple abilities of perceiving and expressing emotion. In contrast/ the highest level branch concerns the conscious/ reflective regulation of emotion".

LANGUAGE & THOUGHT

Language

Language is a cognition that truly makes us human. Language can be described as a "tool of thought" but we usually think of it as a tool of communication among people. Whereas other species do communicate with an innate ability to produce a limited number of meaningful vocalizations, there is no other species known to date that can express infinite ideas (sentences) with a limited set of symbols (speech sounds and words). Language is said to communicate when others understand the meaning of our sentences, and we, in turn/ understand theirs.

Linguistic Competence

When we speak one of the thousands of languages of the words, we draw on our inner knowledge of the rules governing the use of language. This knowledge about language is called linguistic competence.

Linguistics is the study of languages as structured systems of rules, it also studies the origin of languages, the relationships among languages, how languages changes over time, and the nature of language sounds.

Language Elements

Starting with the basic sounds of speech, spoken language can be broken down into these elements:

Phones and Phonemes: Speech sounds, or phones, are made by adjusting the vocal cords and moving the tongue, lips and mouth in different precise ways. Hundreds of speech sounds can be distinguished on the basic of their frequency their intensity and their pattern of vibrations over - time. Only a limited number of all the possible phones are important to the understanding of speech, these are known as phonemes. English has 46 separate phonemes, a, e, i, o, u, consonant as p, m, k and d and blends of the two.

Syllables: When two or three phonemes are combined, it converts into a syllable. The syllable is the smallest unit of speech perception.

Morphemes: Morphemes are the smallest units of speech perception or language that convey meaning. These are root words that can stands alone. Morphemes can be prefixes, words, or suffixes. English has about 100,000 morphemes.

Words, Clauses and Sentences: Words are combined by the rules of grammar into clauses, and clauses are formed into sentences. A clause consists of a verb and its associated nouns, adjectives and so on. Clauses are the major units of perceived meaning in speech.

Theories of Language Development

The Learning Perspective: The Learning perspective argues that children imitate what they see and hear, and that children learn language by trying various combinations of sounds and being rewarded by their parents and others for those sounds that represent true language. Skinner argued that adults shape the speech of children by reinforcing the babbling of infants that sound most like words.

The Nativist Perspective: The nativist perspective argues that humans are biologically programmed to gain knowledge. The main theorist associated with this perspective is Noam Chomsky.

Chomsky proposed that all humans have language acquisition device (LAD). The LAD contains knowledge of grammatical and syntactic rules common to all languages. The LAD also allows children to understand the rules of whatever language they are listening to. Chomsky also developed the concepts of transformational grammar, surface structure, and deep structure.

Transformational grammar is grammar that transforms a sentence. Surface structures are words that are actually written Deep structure is the underlying message or meaning of a sentence.

Interactionist Theory: Interactionists argue that language development is both biological and social. Interactionists argue that language learning is influenced by the desire of children to communicate with others. These theories focus mainly on the caregiver's attitudes and attentiveness to their children in order to promote productive language habits.

The Interactionists argue that "children are born with a powerful brain that matures slowly and predisposes them to acquire new understandings that they are motivated to share with others". The main theorist associated with interactionist theory is Lev Vygotsky. Interactionists focus on Vygotsky's model of collaborative learning. Collaborative learning is the idea that conversations with order people can help children both cognitively and linguistically.

Basic Components of Language

Phonological development: Phonology involves the rules about the structure and sequence of speech sound. It stands form shortly after birth to around one year. At around two months, the baby will engage in cooing, which mostly consists of vowel sounds. At around four months cooing rums into babbling which is the repetitive consonant-vowel combinations. Once the child enters the 8-12 month range the child engages in canonical babbling i.e. dada as well as variegated babbling. From 12-24 months, babies can recognise the correct pronunciation of familiar words. Babies will also use phonological strategies to simplify word pronunciation. Within the first year, two word utterances and two syllable words emerge. This period is often called the holophrastic stage of development, because one word conveys as much meaning as an entire phrase. For instance/ the simple word "milk" can imply that the child is requesting milk.

Semantic development: Semantics consists of vocabulary and how concepts are expressed through words. From birth to one year, comprehension (the language we understand) develops before production (the language we use). There is about a 5 month lag in between the two. Babies have an innate preference to listen to their mother's voice. Babies can recognise familiar words and use preverbal gestures. Within the first 12-18 months semantic roles are expressed in one word speech including agent, object, location, possession, nonexistence and denial. Words are understood outside of routine games but the child still needs contextual support for lexical comprehension.

Grammatical development

Grammar involves two parts.

From 1-2 years, children start using telegraphic speech, which are two word combinations, for example 'wet diaper'. Brown (1973) observed that 75% of children's two-word utterances could be summarised in the existence of 11 semantic relations:

Pragmatics development: Pragmatics involves the rules for appropriate and effective communication. Pragmatics involves three skills:

Using language for greeting, demanding etc.

Changing language for talking differently depending on who it is you are talking to;

Following rules such as turn taking, staying on topic.

Language Disorders

Mutism: Mutism refers to total absence of speech. There could be complete or partial mutism depending on the absence or decreased speech output. There could be children with hearing impairment.

Aphasia: Aphasia in children is the problems in understanding and using spoken language without any hearing loss, mental retardation, any other physical or emotional impairment in the use of language as a result of brain injury in the foetal period. These children have problems in understanding what is said to them and talking inspite of having normal sensory skills as hearing, vision, normal intelligence and good emotional adjustment.

Articulation Problems: Children learn to utter/articulate/pronounce vowels like a/, i/, u/, o/, e, etc. first by 2-3 years and then acquire the consonants like p/t/k/ etc. later. The normal production of speech sounds viz. vowels and consonants with the appropriate movements of tongue, lips, jaw and other oral structure is articulation.

|

Approx. age |

Sound mastered |

|

2 |

b p m |

|

3 |

d t n g k n ng yj |

|

4 |

f l

|

|

5 |

v s h |

|

6 |

s z r h

|

Omission Errors refer to omitting or deleting a particular sound in a word as in fi for fish.

Substitution Errors refer to substituting one sound for another as in tan for san (son).

Distortion Errors is where the sound is uttered nearer to the target sound but is not exactly the target sound for example fiyth for fish.

Addition Errors is where a new sound is added to sounds of a word as iskool for skuul (School).

Stuttering: It refers to the involuntary repetition, prolongation pauses or hesitation which the child struggles to end. Child has no conscious control over these blocks and hence they may be called involuntary.

Cluttering is a speech disorder characterized by an extremely rapid rate of speaking often with articulation errors.

THINKING

The mind is the idea while thinking processes of the brain involved in processing information such as when we form concepts, engage in problem solving, to reason and make decisions. Some limit the definition of thinking is as follows

1. Thinking is the activity of human reason as a process of strengthening the relationship between stimulus and response:

2. Thinking is a reasonable working various views with the knowledge that has been stored in the mind long before the emergence of new knowledge.

3. Thinking can be interpreted to remember something, and questioned whether there is a relationship between what is intended.

4. Thinking is exploring substantive psychic awareness of human nature.

5. Thinking is processing information mentally or cognitively by rearranging the information from the environment and the symbols are stored in the memory of his past.

6. Thinking is a symbolic representation of some event train of ideas in a precise and careful that began with the problem.

7. Thinking is mental representations newly formed through the transformation of information by interaction attributes such as the assessment of mental abstraction logic, imagination and problem solving.

.

.

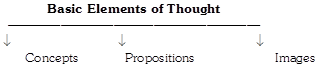

Concepts: Concepts are mental categories for objects, events, experiences, or ideas that are similar to one another in one or more respects. Concepts are closely related to schemas. Schemas are cognitive frameworks that represent our knowledge of and assumptions. Artificial concepts are ones that can be clearly defined by a set of rules or properties. Thus a tomato is a fruit because it possesses the properties established by botanists for this category.

In contrast, natural concepts are ones that have no fixed and readily specified set of defining features. They are fuzzy around the edges. For example, consider the following questions:

Is a pickle a vegetable?

Is chess a sport?

As you can readily see, these all relate to common concepts; sport, vegetable. But what specific attributes are necessary for inclusion in each concept.

Natural concepts are often based on prototypes. Prototypes are the best or cleasest examples of various objects or stimuli in the physical world.

Propositions: Propositions are sentences that relate one concept to another and can stand as separate assertions. For example, consider the following propositions.

Politicians are often self-serving. Concepts play a key role in politicians and self-serving.

Images: Images are mental pictures of the world. Mental images serve important purposes in thinking. People report using them for understanding verbal instructions, by converting the words into mental pictures of actions, for increasing motivation, by imagining successful performance, and for enhancing their own moods, by visualizing positive events or scenes.

LANGUAGE AND THOUGHT

Do we think what we say or say what we think?

What is the precise relationship between language and thought? There are two possibilities:

1. Language Shapes Thought

One possibility, known as the linguistic relativity hypothesis, suggests that language actually shapes or determines thought (Whorf, 1956). According to this view, people who speak different languages may actually perceive the world in different ways because their thinking is determined by the words available to them. For example, Eskimos, who have many different words to describe snow, may actually perceive this aspect of the physical world differently from English speaking people who have only one word.

2. Thought Shapes Language

Other possibility, known as the linguistic relativity approach (Miura & Okamoto, 1989) suggests that thought shapes language. This position suggests that language merely reflects the way we think..

You need to login to perform this action.

You will be redirected in

3 sec