NCERT Extracts - Bhakti - Sufi Tradition

Category : UPSC

The Alvars and Nayanars of Tamil Nadu

- Alvars - literally, those who are "immersed" in devotion to Vishnu.

- Nayanars - literally, leaders who were devotees of Shiva.

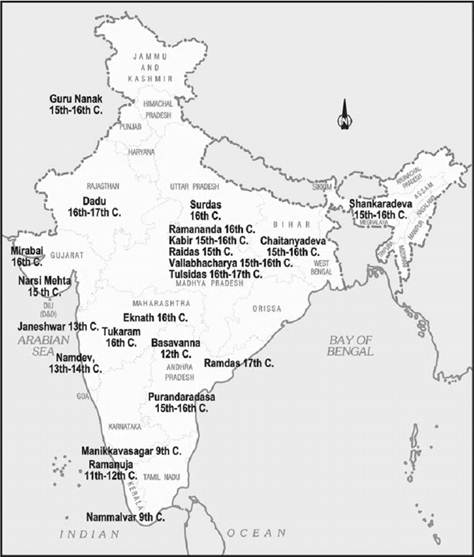

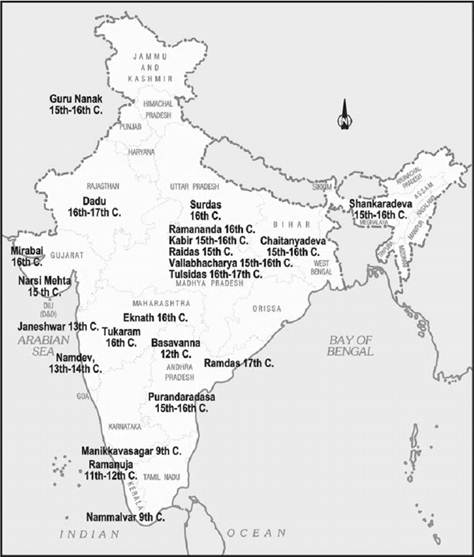

- Some of the earliest bhakti movements (c. sixth century) were led by the Alvars and Nayanars.

- Alvars and Nayanars saints came from all castes including those considered "^untouchable" like the Pulaiyar and the Panars.

- They travelled from place to place singing hymns in Tamil in praise of their gods.

- During their travels the Alvars and Nayanars identified certain shrines as abodes of their chosen deities. Very often large temples were later built at these sacred places.

- These developed as centres of pilgrimage. Singing compositions of these poet-saints became part of temple rituals in these shrines, as did worship of the saints' images.

- There were 63 Nayanars, who belonged to different caste backgrounds such as potters, "untouchable" workers, peasants, hunters, soldiers, Brahmanas and chiefs.

- The best known among them were Appar, Sambandar, Sundarar and Manikkavasagar.

- There are two sets of compilations of their songs -Tevaram and Tiruvacakam.

- There were 12 Alvars, who came from equally divergent backgrounds, the best known being Periyalvar, his daughter Andal, Tondaradippodi Alvar and Nammalvar.

- Their songs were compiled in the Divya Prabandham.

Women devotees : Andal and Karaikkal Ammaiyar

- The compositions of Andal, a woman Alvar, were widely sung.

- Andal saw herself as the beloved of Vishnu; her verses express her love for the deity.

- Another woman, Karaikkal Ammaiyar, a devotee of Shiva, adopted the path of extreme asceticism in order to attain her goal. Her compositions were preserved within the Nayanar tradition.

- By the tenth century the compositions of the 12 Alvars were compiled in an anthology known as the Nalayira Divyaprabandham (“four Thousand Sacred Compositions”).

- The poems of Appar, Sambandar and Sundarar form the Tevaram, a collection that was compiled and classified in the tenth century on the basis of the music of the songs.

The Virashian Tradition in Karuataka

- The twelfth century witnessed the emergence of a new movement in Karnataka, led by a Brahmana named Basavanna (1106-68)

- He was initially a Jaina and a minister in the court of a Chalukya king. His followers were known as Virashaivas (heroes of Shiva) or Lingayats (wearers of the linga).

- Lingayats continue to be an important community in the region to date. They worship Shiva strung over the left shoulder.

- The Lingayats challenged the idea of caste and the "pollution" attributed to certain groups by Brahmanas. They also questioned the theory of rebirth. These won them followers amongst those who were marginalised within the Brahmanical social order.

- Our understanding of the Virashaiva tradition is derived from vachanas (literally, sayings) composed in Kannada by women and men who joined the movement.

The Popular Practice of Islam

- The developments that followed the coming of Islam were not confined to ruling elites; in fact they permeated far and wide, through the subcontinent, amongst different social strata

- All those who adopted Islam accepted, in principle, the five “pillars" of the faith: that there is one God, Allah, and Prophet Muhammad is his messenger (shahada); offering prayers five times a day (namaz/salat); giving alms (zakat); fasting during the month of Ramzan (sawm); and performing the pilgrimage to Mecca (hajj).

- However, these universal features were often overlaid with diversities in practice derived from sectarian affiliations (Sunni, Shia), and the influence of local customary practices of converts from different social milieus.

- The Khojahs, a branch of the Ismailis (a Shia sect), developed new modes of communication, disseminating ideas derived from the Quraan through indigenous literary genres.

- These included the ginan (derived from Ac Sanskrit jnana, meaning "knowledge"), devotional poems in Punjabi, Multani, Sindhi, Kachchi, Hindi and Gujarati, sung in special ragas during daily prayer meetings.

- Arab traders who settled along the Malabar coast adopted the local language, Malayalam.

- They also adopted local customs such as matriliny and matrilocal residence.

- The complex blend of a universal faith with local traditions is perhaps best exemplified in the architecture of mosques.

- Some architectural features of mosques are universal - such as their orientation towards Mecca, evident in the placement of the mihrab (prayer niche) and the minbar (pulpit).

- However, there are several features that show variations - such as roofs and building materials.

The Growth of Sufism

Sufis were Muslim mystics.

- In the early centuries of Islam a group of religious minded people called sufis turned to asceticism and mysticism in protest against the growing materialism of the Caliphate as a religious and political institution,

- They were critical of the dogmatic definitions and scholastic methods of interpreting the Qur’an and sunna (traditions of the Prophet) adopted by theologians.

- Instead, they laid emphasis on seeking salvation through intense devotion and love for God by following His commands, and by following the example of the Prophet Muhammad whom they regarded as a perfect human being.

- The sufis thus sought an interpretation of the Qur'an on the basis of their personal experience.

- Some of the early Sufis, such as the woman mystic Rabia (eight century), and Mansur bin Hallaj (tenth century) laid great emphasis on love as the bond between God and the individual soul.

- But their pantheistic approach led them into conflict with the orthodox elements who had Mansur executed for heresy.

- Despite his setback, mystic ideas continued to spread among the Muslim masses.

- Al-Ghazzali (d. 1112), who is venerated both by the orthodox elements and the Sufis, tried to reconcile mysticism with Islamic orthodoxy.

Khanqahs and silsilas

- By the eleventh century Sufism evolved into a well developed movement with a body of literature on Quranic studies and sufi practices.

- Institutionally, the sufis began to organise communities around the hospice or khanqah (Persian) controlled by a teaching master known as shaikh (in Arabic), pir or murshid (in Persian). He enrolled disciples (murids) and appointed a successor (khalifa).

- He established rules for spiritual conduct and interaction between inmates as well as between laypersons and the master.

- Sufi silsilas began to crystallise in different parts of the Islamic world around the twelfth century.

- The word silsila literally means a chain, signifying a continuous link between master and disciple, stretching as an unbroken spiritual genealogy to the Prophet Muhammad.

- When the shaikh died, his tomb-shrine (dargah, a Persian term meaning court) became the centre of devotion for his followers.

- This encouraged the practice of pilgrimage or ziyarat to his grave, particularly on his death anniversary or urs (or marriage, signifying the union of his soul with God).

- This was because people believed that in death saints were united with God, and were thus closer to Him than when living. People sought their blessings to attain material and spiritual benefits. Thus evolved the cult of the shaikh revered as

Outside the khanqah

- Some mystics initiated movements based on a radical interpretation of sufi ideals.

- Many scorned the khanqah and took to mendicancy and observed celibacy.

- They ignored rituals and observed extreme forms of asceticism.

- They were known by different names - Qalandars, lyiadaris, Malangs, Haidaris, etc. Because of their deliberate defiance of the shaaa they were often referred to as be-sharia, in contrast to the ba-sharia sufis who compliet with it.

Sufism and tasawwuf

- Sufism is an English word coined in the nineteenth century.

- The word used for Sufism in Islamic texts is tasawwuf.

- Historians have understood this term in several ways. According to some scholars, it is derived from suf, meaning wool, referring to the coarse woollen clothes worn by sufis. Others derive it from safa, meaning purity.

- It may also have been derived from suffa, the platform outside the Prophet's mosque, where a group of close followers assembled to leam about the faith.

Names of silsilas

- Most sufi lineages were named after a founding figure. For example, the Qadiri order was named after Shaikh Abd'ul Qadir Jilani.

- Wali (plural auliya) or friend of God was a sufi who claimed proximity to Allah, acquiring His Grace (barakat) to perform miracles (karamat).

- The Sufis were organised in 12 orders of silsilahs.

- The Sufi orders are broadly divided into two: Ba-shara, that is, those who followed the Islamic Law (shara) and Be-shara, that is, those who were not bound by it.

- Of the Be-shara movements, only two acquired significant influence in north India during the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries. These were the Chishti and Suharwardi silsilahs.

The Chishti Silsilahs

- After staying for some time in Lahore and Delhi, Khwaja Muinuddin Chishti finally shifted to Ajmer.

- Among the disciples of Shaikh Muinuddin (d. 1235) were Bakhtiyar Kaki and his disciple Farid-ud-Din Ganj-i-Shakar.

- Farid-ud-Din confined his activities to Hansi and Ajodhan (in modem Haryana and the Punjab, respectively).

- His verses are later found quoted in the Adi-Granth of the Sikhs.

- The most famous of the Chishti saints, however, were Nizamuddin Auliya and Nasiruddin Chiragh-i-Delhi.

- Nizamuddin Auliya adopted yogic breathing exercises, sp much so that the yogis called him a sidh or 'perfect'.

Suharwardi order

- The Suharwardi order entered India at about the same time, as the Chishtis, but its activities were confined largely to the Punjab and Multan.

- The most well-known saints of the order were Sheikh Shihabuddin Suharwardi and humid-up-Din Nagori Hamid-.

- Unlike the Chishtis, the Suharwardi saints did not believe in leading a life of poverty.

- They accepted the service of the state, and some of them held important posts in the ecclesiastical department.

- The Chishtis, on the other hand, preferred to keep aloof from state politics and shunned the company of rulers and nobles.

- The Chishti order was established in India by Khwaja Muinuddin Chishti who came to India around 1192.

Life in the Chishti khanqah

- The khanqah was the centre of social life.

- We know about Shaikh Nizamuddin's hospice (c. fourteenth century) on the banks of the river Yamuna in Ghiyaspur, on the outskirts of what was then the city of Delhi.

- The Shaikh lived in a small room on the roof of the hall where he met visitors.

- On one occasion, fearing a Mongol invasion, people from the neighbouring areas flocked into the khanqah to seek refuge.

- From morning till late night people from all walks of life - soldiers, slaves, singers, merchants, poets, travellers, rich and poor, Hindu jogis (yogi) and qalandars – came seeking discipleship, amulets for healing, and the intercession of the Shaikh in various matters.

- Other visitors included poets such as Amir Hasan Sijzi and Amir Khusrau and the court historian Ziyauddin Barani, all of whom wrote about the Shaikh.

- Shaikh Nizamuddin appointed several spiritual successors and deputed them to set up hospices in various parts of the subcontinent.

Chishti devotionalism : ziyarat and qawwali

- Pilgrimage, called ziyarat, to tombs of sufi saints is prevalent all over the Muslim. world. This practice is an occasion for seeking the sufi's spiritual grace.

- For more than seven centuries people of various creeds, classes and social backgrounds have expressed their devotion at the dargahs of the five great Chishti saints.

- Amongst these, the most revered shrine is that of Khwaja Muinuddin, popularly known as "Gharib Nawaz" (comforter of the poor).

- Muhammad-bin-Tughlaq was the first Sultan to visit the shrine.

- By the sixteenth century the shrine had become very popular; in fact it was the spirited singing of pilgrims bound for Ajmer that inspired Akbar to visit the tomb.

- Also part of ziyarat is the use of music and dance including mystical chants performed by specially trained musicians or qawwals to evoke divine ecstasy.

- Sama was integral to the Chishtis, and exemplified interaction with indigenous devotional traditions.

- The dargah of Shaikh Salim Chishti (a direct descendant of Baba Farid) constructed in Fatehpur Sikri, Akbar's capital, symbolised the bond between the Chishtis and the Mughal state.

- Baba Farid composed verses in the local language, which were incorporated in the Guru Granth Sahib.

- Yet others composed long poems or masnavis to express ideas of divine love using human love as an allegory.

- For example, the prem-akhyan (love story) Padmavat composed by Malik Muhammad Jayasi revolved around the romance of Padmini and Ratansen, the king of Chittor.

- It is likely that the sufis of this region were inspired by the pre-existing bhakti tradition of the Kannada vachanas of the Lingayats and the Marathi abhangs of the sants of Pandharpur.

Sufis and the state

- A major feature of the Chishti tradition was austerity, including maintaining a distance from worldly power.

- However, this was by no means a situation of absolute isolation from political power.

- The sufis accepted unsolicited grants and donations from the political elites.

- The Sultans in turn set up charitable trusts (auqaf ) as endowments for hospices and granted tax-free land (inam). The Chishtis accepted donations in cash and kind.

- Occasionally the sufi shaikh was addressed with high-sounding titles. For example, the disciples of Nizamuddin Auliya addressed him as sultan-ul-mashaikh (literally, Sultan amongst shaikhs).

Major Teachers of the Chishti Silsila

|

Sufi Teachers

|

Year of Death

|

Location of Dargah

|

|

· Shaikh Muinuddin Sijvi

|

1235

|

Ajmer (Rajasthan)

|

|

· Khwaja Qutbuddin Bakhtiyar kaki

|

1235

|

Delhi

|

|

· Shaikh Fariduddin Ganj-i Shakar

|

1265

|

Ajodhan (Pakistan)

|

|

· Shaikh Nizamuddin Auliya

|

1325

|

Delhi

|

|

· Shaikh Nasiruddin Chiragh-I

|

1365

|

Delhi

|

- Hujwiri died in 1073 and was buried in Lahore. The grandson of Sultan Mahmud of Ghazni constructed a tomb over his grave, and this tomb-shrine became a site of pilgrimage for his devotees, especially on his death anniversary.

- Even today Hujwiri is revered as Data Ganj Bakhsh or "Giver who bestows treasures" and his mausoleum is called Data Darbar or "Court of the Giver".

- Munis al Arwah (The Confidant of Spirits) is Jahanara's biography of Shaikh Muinuddin Chishti

- This is what an eighteenth-century visitor from the Deccan, Dargah Quii Khan, wrote about the shrine of Nasiruddin Chiragh-i Dehli in his Muraqqa-i Dehli (Album of Delhi) : "The Shaikh (in the grave) is not the lamp of Delhi but of the entire country. People turn up there in crowds, particularly on Sunday. They take baths to obtain cures from chronic diseases. Muslims and Hindus pay visits in the same spirit."

Naqshbandi school

- Among the Muslims, too, while the trend oftauhid continued apace, and was supported by many leading Sufi saints, a small group of the orthodox ulama reached against it and the liberal policies of Akbar.

- The most renowned figure in the Muslim orthodox and revivalist movement of the time was Shaikh Ahmad Sirhindi.

- A follower of the orthodox Naqshbandi school of Sufis which had been introduced in India during Akbar's reign.

- Shaikh Ahmad Sirhindi opposed the concept of pantheistic mysticism (tauhid) or the belief in the unity of Godhead, denouncing it as un-Islamic.

- However, the ideas of Shaikh Ahmad had little impact. Jahangir imprisoned him for claiming a status beyond that of the Prophet.

- It will thus be seen that the influence of the orthodox thinkers and preachers was limited, being necessarily confined to narrow circles.

- The recurrent cycles of liberalism and orthodox in Indian history should be seen against the situation which was rooted in the structure of Indian society.

- The prestige and influence of the narrow, orthodox elements and their re-assertion of narrow ideas and beliefs was a barrier to the growing process of rapprochement and tolerance among the votaries of the two dominant religions, Hinduism and Islam, and a hindrance to the process of cultural integration.

Amir Khusrau

- Amir Khusrau was bom in 1252 at Patiali near Badayun in western Uttar Pradesh.

- He was a great poet, musician and disciple of Shaikh Nizamuddin Auliya.

- He gave a unique form to the Chishti sama by introducing the qaul (Arabic word meaning "saying"), a hymn sung at the opening or closing of qawwali.

- This was followed by sufi poetry in Persian, Hindavi or Urdu, and sometimes using words from all of these languages.

- Qawwals (those who sing these songs) at the shrine of Shaikh Nizamuddin Auliya always, start their recital with the qaul. Qawwali is performed in shrines all over the subcontinent.

- Khusrau wrote a large number of poetical works, including historical romances

- He experimented with all the poetical forms and created a new style of Persian which came to be called the sabaq-i-hindi or the style of India.

- Khusrau has praised the Indian languages, including Hindi (which he calls Hindavi).

- Some of his scattered Hindi verses are found, though the Hindi work, Khaliq Bari, often attributed to Khusrau.

- Khusrau was given the title of nayak or master of both the theory and practice of music

- He introduced many Peros-Arabic airs (ragas), such as aiman, ghora, sanam, etc.

- He is credited with having invented the sitar, though we have no evidence of it.

- The tabia which is also attributed to him seems, however, to have developed during the late seventeenth or early eighteenth century.

- Khusrau, it is said, gave up his life the day after he leamt of the death of his pir, Nizamuddin Auliya (1325). He was buried in the same compound.

Bhakti Traditions

- Many poet-saints engaged in explicit and implicit dialogue with these new social situations, ideas and institutions. Let us now see how this dialogue found expression.

- Maharashtrian saint, Namadeva flourished in the first part of the fourteenth century

- Namadeva was a tailor who had taken to banditry before he became a saint.

- His poetry, written in Marathi, breathes a spirit of intense love and devotion to God.

- Namadeva is said to have travelled far and wide and enagged in discussions with the Sun saints in Delhi.

- Ramananda, is placed in the second half of the fourteenth and first quarter of the fifteenth century.

- Ramananda who was a follower of Ramanuja, was born prayag (Allahbad) and lived there and at Banaras. He substituted the the Worship of rama in place of Vishnu.

- Wnat is more, he taught his doctrine of Bhakti to all the four varnas, and disregarded the ban on people of different castes cooking or eating their meals together.

- He enrolled disciples from all castes, including the low castes.

- Thus his disciples included Ravidas, who was a cobbler; Kabir weaver, Sena who was a barber; and Sadhana, who was a butcher.

- Namadeva was equally broad-minded in enrolling his disciples.

- These coincided with the Islamic ideas of equality and brotherhood which had been preached by the Sufi saints.

- People were no longer satisfied with the old religion; they wanted a religion which could satisfy both their reason and emotions.

- It was due to these factors that the Bhakti movement became a popular movement in north India during the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries.

Weaving a divine fabric : Kabir (c. fourteenth-fifteenth centuries)

- Kabir is perhaps one of the most outstanding examples of a poet-saint who emerged within this context. There is good deal of uncertainty about the dates and early life of Kabir.

- Hagiographies within the Vaishnava tradition attempted to suggest that he was bom a Hindu, Kabirdas (Kabir itself is an Arabic word meaning "great"), but was raised by a poor Muslim family belonging to the community of weavers who were relatively recent converts to Islam. He learned the profession of his adopted father.

- While living at Kashi, he came in contact with both the Hindu and Muslim saints.

- Kabir emphasised the unity of God whom he calls by several names, such as Rama, Hari Govinda, Allah, Sain, Sahib, etc.

- The Kabir Bijak is preserved by the Kabirpanth (the path or sect of Kabir) in Varanasi and elsewhere in Uttar Pradesh.

- The Kabir Granthavali is associated with the Dadupanth in Rajasthan, and many of his compositions are found in the Adi Granth Sahib.

- Kabir's poems have survived in several languages and dialects; and some are composed in the special language of nirguna poets, the sant bhasha.

- Others, known as ulatbansi (upside-down sayings), are written in a form in which everyday meanings are inverted. These hint at the difficulties of capturing the nature

- the Ultimate Reality in words : expressions such as "the lotus which blooms

- without flower" or the "fire raging in the ocean" convey a sense of Kabir "s mystical experiences.

- Also striking is the range of traditions Kabir drew on to describe the Ultimate Reality.

- These include Islam: he described the Ultimate Reality as Allah, Khuda, Hazrat and Pir.

- He also used terms drawn from Vedantic traditions, alakh (the unseen), nirakar (formless), Brahman, Atman, etc.

- It is suggested that he was initiated into bhakti by a guru, perhaps Ramananda.

- Historians have pointed out that it is very difficult to establish that Ramananda and Kabir were contemporaries, without assigning improbably long lives to either or both.

- Kabir strongly denounced idol-worship, pilgrimages, bathing in holy rivers or taking part in formal worship, such as namaz.

- Though familiar with yogic practices, he considered neither asceticism nor book knowledge important for true knowledge.

- He rejected those features of Hinduism and Islam which were against this spirit and which were of no importance for the real spiritual welfare of the individual."

- Kabir strongly denounced the caste system, especially the practice of untouchability, and emphasized the fundamental unity of man.

- He upheld the fundamental unity of man, and was opposed to all kinds of discrimination between human beings, whether on the basis of castes, or religion, race, family or wealth.

- However, he was not a social reformer, his emphasis being reform of the individual under the guidance of a true guru or teacher.

Baba Guru Nanak and the Sacred Word

- Guru Nanak (1469-1539) was bom in a Hindu merchant family in the village of Talwandi (now called Nankana Sahib) on the bank of the river Ravi.

- He trained to be an accountant and studied Persian. He was married at a young age but he spent most of his time among sufis and bhaktas.

- It is said that Nanak undertook wide tours all over India and, even beyond it.

- He established a centre at Kartarpur (Dera Baba Nanak on the river Ravi).

- The sacred space created by him was known as dharmsal. It is now known as Gurdwara.

- The message of Baba Guru Nanak is spelt out in his hymns and teachings. These suggest that he advocated a form of nirguna bhakti.

- He composed hymns and sang them to the accompaniment of the rabab, a stringed instrument played by his faithful attendant, Mardana

- He firmly repudiated the external practices of the religions he saw around him.

- He rejected sacrifices, ritual baths, image worship, austerities and the scriptures of both Hindus and Muslims.

- He emphasized the importance of the worship of one God.

- His idea of liberation was not that of a state of inert bliss but rather the pursuit of active life with a strong sense of social commitment.

- He himself used the terms nam, dan and isnan for the essence of his teaching, which actually meant right worship, welfare of others and purity of conduct.

- His teachings are now remembered as nam-japna, kirt-karna and vand-chhakna, which also underline the importance of right belief and worship, honest living, and helping others.

- Like Kabir, Nanak laid emphasis on the one God, by repeating whose name and dwelling on it with love and devotion one could get salvation without distinction of caste, creed or sect.

- He advocated a middle path in which spiritual life could be combined with the duties of the householder. He organised his followers into a community.

- He set up rules for congregational worship (sangat ) involving collective recitation.

- His followers ate together in the common kitchen, called

- Before his death, Guru Nanak appointed one of his followers 'Lehna' as his successor.

- Lehna came to be known as Guru Angad.

- The fifth preceptor, Guru Arjan, compiled Baba Guru Nanak's hymns along with those of his four successors and other religious poets like Baba Farid, Ravidas (also known as Raidas) and Kabir in the Adi Granth Sahib.

- These hymns, called "gurbani", are composed in various languages.

- The tenth preceptor, Guru Gobind Singh, included the compositions of the ninth guru, Guru Tegh Bahadur, and this scripture was called the Guru Granth Sahib.

- Guru Granth Sahib is the holy scripture of the Sikhs.

- The Mughal emperor Jahangir looked upon them as a potential threat and he ordered the execution of Guru Arjan in 1606.

- The Sikh movement began to get politicized in the seventeenth century, a development which culminated in the institution of the Khalsa Panth by Guru Gobind Singh in 1699.

- The Khalsa Panth (army of the pure) became a political entity.

- Guru Gobind Singh defined its five symbols : uncut hair, a dagger, a pair of shorts, a comb and a steel bangle.

- Under him the community got consolidated as a socio-religious and military force.

Mirabai, the devotee princess

- Mirabai (c. fifteenth-sixteenth centuries) is perhaps the best-known woman poet within the bhakti tradition.

- Biographies have been reconstructed primarily from the bhajans attributed to her, which were transmitted orally for centuries.

- According to these, she was a Rajput princess from Merta in Marwar. who was married against her wishes to a prince of the Sisodia clan of Mewar, Rajasthan.

- She defied her husband and did not submit to the traditional role of wife and mother, instead recognising Krishna, the avatar of Vishnu, as her lover.

- Her in-laws tried to poison her, but she escaped from the palace to live as a wandering singer composing songs that are characterised by intense expressions of emotion.

- Mirabai became a disciple ofRavidas, a saint from a caste considered "untouchable", This indicate her defiance of the norms of caste society.

- After rejecting the comforts of her husband's palace, she is supposed to have donned the white robes of a widow or the saffron robe of the renouncer.

- She was devoted to Krishna and composed bhajans expressing her intense devotion.

- Her songs also openly challenged the norms of the "upper" castes and became popular with the masses in Rajasthan and Gujarat.

- Her songs continue to be sung by women and men, especially those who are poor and considered "low caste" in Gujarat and Rajasthan.

- Although Mirabai did not attract a sect or group of followers, she has been recognized as a source of inspiration for centuries.

Shankaradeva (fifteenth century)

- Shankaradeva was one of the leading proponents of Vaishnavism in Assam.

- His teachings, often known as the Bhagavati dharma because they were based on the Bhagavad Gita and the Bhagavata Purana, focused on absolute surrender to the supreme deity, in this case Vishnu.

- He emphasised the need for naam kirtan, recitation of the names of the lord in sat sanga or congregations of pious devotees.

- He also encouraged the establishment of satra or monasteries for the transmission of spiritual knowledge, and naam ghar or prayer halls.

- Many of these institutions and practices continue to flourish in the region. His major compositions include the Kirtana-ghosha.

The Vaishnavite Movement

- The Bhakti movement in north India developed around the worship of Rama and Krishna, two of the incarnations of the god Vishnu.

- The childhood escapades of the boy Krishna and his dalliance with the milk-maids of Gokul, especially with Radha became themes of a remarkable series of saint-poets who lived and preached during the 15th and early 16th centuries.

- Chaitanya popularised musical gathering or kirtan as a special form of mystic experience in which the outside world disappeared by dwelling on God's name.

- According to Chaitanya, worship consisted of love and devotion and song and dance which produced a state of ecstasy in which the presence of God, whom he called hari, could be realised.

- Such a worship could be carried out by all, irrespective of caste and creed.

- The writings of Narsinha Mehta in Gujarat of Meena in Rajasthan, of Surdas in western Uttar Pradesh and of Chaitanya in Bengal and Orissa reached extraordinary heights of lyrical fervour and of love which transcended all boundaries, including those of caste and creed.

Chaitanya

- Born and schooled in Nadia which was the centre ofVedantic rationalism, Chaitanya's tenor of life was changed when he visited Gaya at the age of 22 and was initiated into the Krishna cult by a recluse.

- He became a god-intoxicated devotee who incessantly uttered the name of Krishna.

- Chaitanya is said to have travelled all over India.

- He did not reject the scriptures or idol-worship, though he cannot be classified as a traditionalist.

- All the saint-poets mentioned above remained within the broad framework of Hinduism.

- Their philosophic beliefs were a brand of Vedantic monism which emphasized the fundamental unity of God and the Created world.

- The Vedantist philosophy had been propounded by a number of thinkers, but the one who probably influenced the saint-poets most was Vallabha, a Tailang brahmana, who lived in the last part of the fifteenth and the early part of the sixteenth century.

- The approach of these saint-poets was broadly humanistic.

- They emphasized thq broadest human sentiments - the sentiments of love and beauty in all their forms.

- Like the other nonsectarians, they were not able to make an effective breach in the caste system.

- However, they softened its rigour and built a platform for unity which could be apprehended by wider sections.

- The Indian Sufis started taking more interest in Sanskrit and Hindi and a few of them, such as Malik Muhammad Jaisi, composed their works in Hindi.

- The use of Hindi songs became so popular that an eminent Sufi, Abdul Wahid Belgrami, wrote a treatise Haqaiq-i-Hindi in which he tried to explain such words as "Krishna", "Murii", "Gopis", "Radha", "Yamuna", etc., in Sufi mystic terms.

- Thus, during the fifteenth and the early part of the sixteenth century, the Bhakti and the Sufi saints had worked out in a remarkable manner a common platform on which people belonging to various sects and creeds could meet and understand each other.

- This was the essential background to the ideas of Akbar and his concept of tauhid or unity of all religions.